I really enjoyed the Easter days - Yummy Chocolate eggs, all my family coming together, and glorious weather.

And some productivity, too: Good Friday was spent playing around with cloth in nice company. Sitting around doing strange things to textiles is just so much more fun when you're not alone in the room.

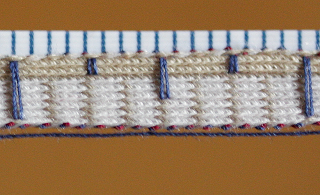

Since Friday was technically a day off, I found the time to play around with wax for sealing and securing cut edges. There are some hints that beeswax was used for this in the middle ages, and I've long wanted to give it a proper try. I did use wax twice before: Once on the kruseler I've made, and once more to seal dagges cut from fine silk cloth. I'm still not sure on how it was done in medieval times, though.

In those first tries, I applied the wax by rubbing some beeswax onto a relatively hot copper plate and then dipping the edge of the fabric into the molten wax. It was pretty hard to control how much wax would come in at once, and it took a rather long time, with uneven wax rims. But it worked, for the straight edges as well as for the oakleaf dagges.

I have recently acquired a tjanting, the Indonesian wax applicator for batik, and I have used that for my last wax application. It is a bit tricky to get the temperature just right (especially when the candle flame used to heat the tjanting is not too cooperative), but it was a lot more convenient than the copper-plate version. And now I'm wondering: In what extent was wax used to neaten and conserve cut edges? With what types of fabric, and in which cases? And how did they apply the wax back in the middle ages - is there a medieval European equivalent to the tjanting that was not yet identified, because nobody expectsthe Spanish Inquisition a wax application tool in a tailoring/silkworking context?

And some productivity, too: Good Friday was spent playing around with cloth in nice company. Sitting around doing strange things to textiles is just so much more fun when you're not alone in the room.

Since Friday was technically a day off, I found the time to play around with wax for sealing and securing cut edges. There are some hints that beeswax was used for this in the middle ages, and I've long wanted to give it a proper try. I did use wax twice before: Once on the kruseler I've made, and once more to seal dagges cut from fine silk cloth. I'm still not sure on how it was done in medieval times, though.

In those first tries, I applied the wax by rubbing some beeswax onto a relatively hot copper plate and then dipping the edge of the fabric into the molten wax. It was pretty hard to control how much wax would come in at once, and it took a rather long time, with uneven wax rims. But it worked, for the straight edges as well as for the oakleaf dagges.

I have recently acquired a tjanting, the Indonesian wax applicator for batik, and I have used that for my last wax application. It is a bit tricky to get the temperature just right (especially when the candle flame used to heat the tjanting is not too cooperative), but it was a lot more convenient than the copper-plate version. And now I'm wondering: In what extent was wax used to neaten and conserve cut edges? With what types of fabric, and in which cases? And how did they apply the wax back in the middle ages - is there a medieval European equivalent to the tjanting that was not yet identified, because nobody expects