It's looking like there will be an exciting fabric reconstruction project in the near future - the very near future, as our time-until-delivery is uncomfortably short. Which, to be fair, is anything less than 12 months for most fabric reconstruction projects.

The issue is that there's a lot of steps involved, and they can take quite a bit of time, plus there's also the lag time for cooperative projects that one has to figure in. And fabric reconstructions are usually cooperative projects, it's rather rare that one single person does all the research, all the spinning, and all the weaving single-handedly.

Fabric reconstruction projects are exciting, and I love them, but they are beasts. Beasts, I can tell you.

First it starts with choosing a fabric - it has to fit the timeframe, and there has to be enough data available on it. Ideally, it's a large enough fragment to get a good impression of yarn style (thickness and regularity or irregularity, though most yarns are pretty evenly spun), how the fabric looks, and it's a jackpot if there's a selvedge involved, though we're not going to get greedy.

Fibre analysis would also be nice, because using a different yarn from a different sheep breed's wool will also make a difference. Not all of the original finds had a fibre analysis done, and that is usually "just" a histogram of thicknesses at best, no information about curl, crimp, or fibre length. Because I don't have a microscope that's really suited to do fibre thickness measurements, I'm also sort of depending on help in that department. Which means... time.

Then there's the first task of finding a suitable modern material, in a suitable form of prep. In theory, one could get the raw fibre and do the prep as part of the project, but then we're talking a few extra months, and a lot of extra hours - probably more than an even generous budget would support. (Unless it's a tiny piece of fabric that is planned to get woven. Once we're in the proper production range, we're quite soon at talking kilograms. Processed, mind you.)

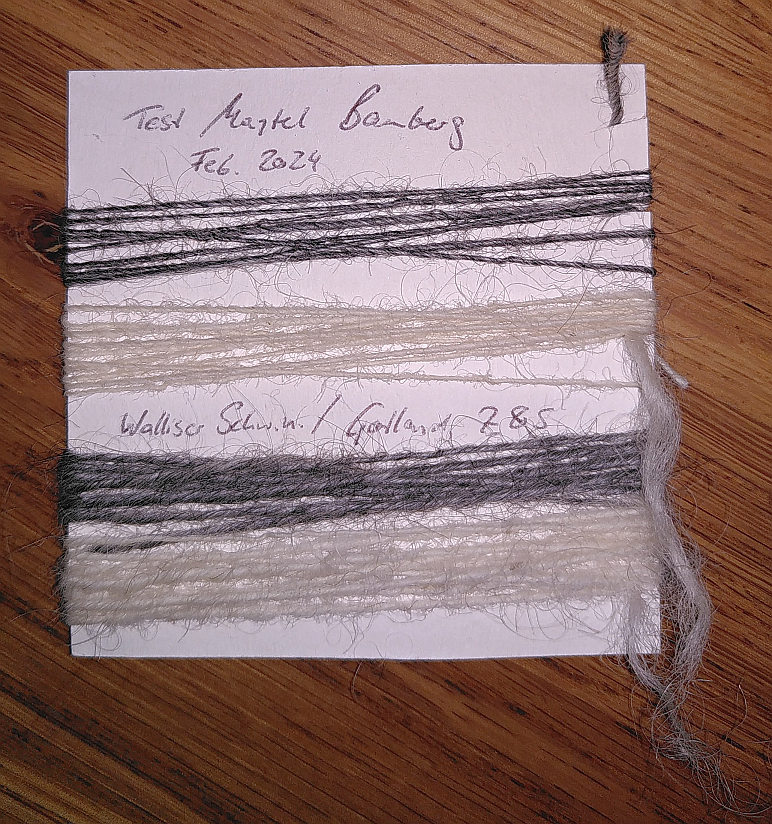

Then there's test spinning, and test weaving, to figure out if things will work out as they are intended to do. Or, to put it better, if there's a good chance they will - if you're a knitter, and have been lied to by one (or more) of your swatches, you'll know exactly what I am getting at. Smaller pieces will give an impression on whether this should be workable or not, or if there's something extremely off, but the big piece will always behave differently than the small test cloth.

Afterwards, there's the spinning - to the specifications that are now more or less fixed, according to the data from the original and the results of the weaving test. And then, as the last step, the Moment of Truth (TM) - the actual weaving of the thing.

Since the last larger project, I have a little excel sheet for calculating the amounts of yarn that I need to spin for a piece with given measurements and thread count, to get a rough estimate of spinning time necessary. Unfortunately, spinning time can also vary quite a lot depending on the yarn style and the fibre, even when using the same spinning tool. (Which in my case, due to time and budget considerations, is usually the e-spinner.) Again, of course I can take the time when I test-spin for the test-weave, and I do - but just like swatches can lie, the test-spinning speed can lie as well. So it's an estimate only, and has to be taken with a grain of salt.

Well, my current calculations say that the fabric might be possible with only about 60 hours of spinning time, plus the test spinning time... that's not too bad, right?

The data I need for the current project-in-the-stage-of-hope will hopefully come together during the next week, and then I will have to get started spinning as quickly as possible. Because in textile reconstruction terms, September is... tomorrow. Keep your fingers crossed for me that things will work out!