I'm back with my Bronze Age Fibre problem. Well, it's not just my problem... it's a pretty common one if you look at reproducing fabrics from that time. Let's take a look...

Modern Merino wool, which is seen as rather fine stuff, has - if of the fine kind - fibre thicknesses of around 20 micron. Sometimes you get extrafine, which is at about 17 micron.

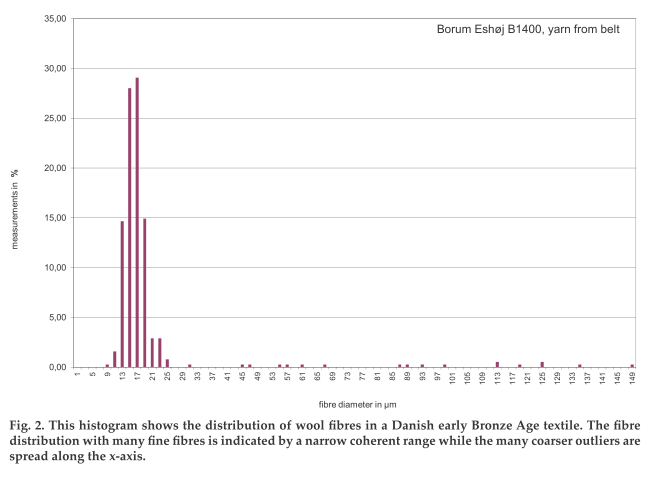

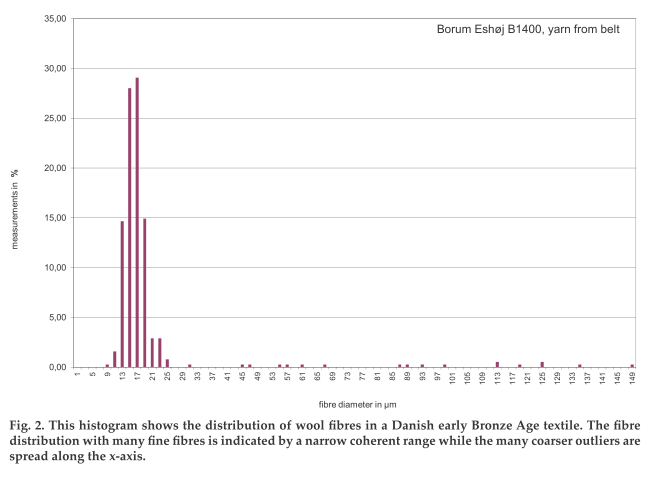

Bronze age fibres were, mostly, around 17 micron. There's fluctuations, of course, but that's the main component of the textiles - really, really fine fibres. Then there's some few extra coarse ones thrown in, with 45-150 micron thickness. A diagram of fibre thicknesses counted was published in Skals, I., & Mannering, U. (2014). Investigating Wool Fibres from Danish Prehistoric Textiles.

Archaeological Textiles Review,

56, 24-34, and thanks to the generousness of ATR,

you can download the whole issue with the article included here. To save you the search, the histogram is on p 26, and it looks like this:

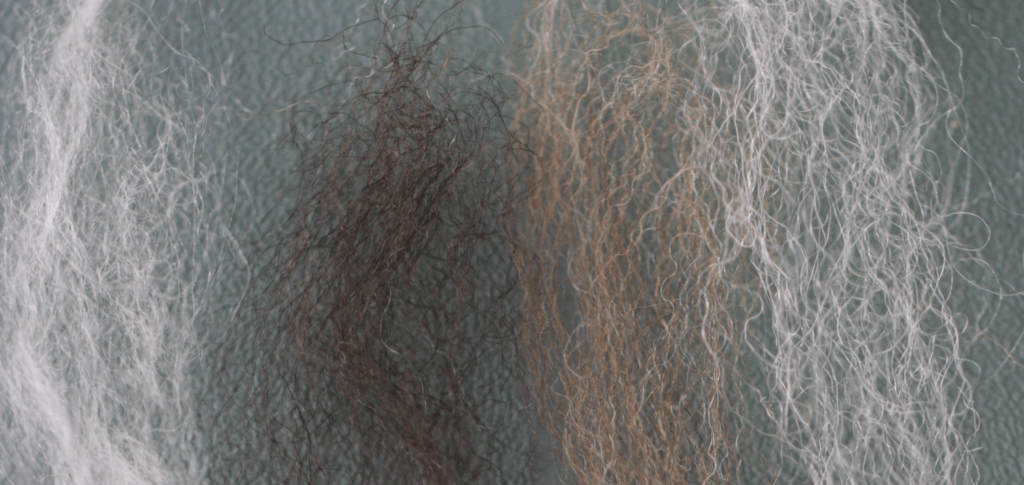

Getting this mix of fibres is difficult these days. I have gotten some superduperfine special wool now, with (according to my supplier) around 15 micron of fibre thickness. You can see it to the very left in this picture; next to it is a sample of my beloved Eider wool, and on the right Valais Blacknose wool.

Even though it's just a macro photograph, I think the difference is quite clear. The difference when you touch it is very clear as well - the superduperfine wool feels like silk, and it's supershiny (which is partly due to some post-shearing treatment), while the Eider and Valais are just normal shiny.

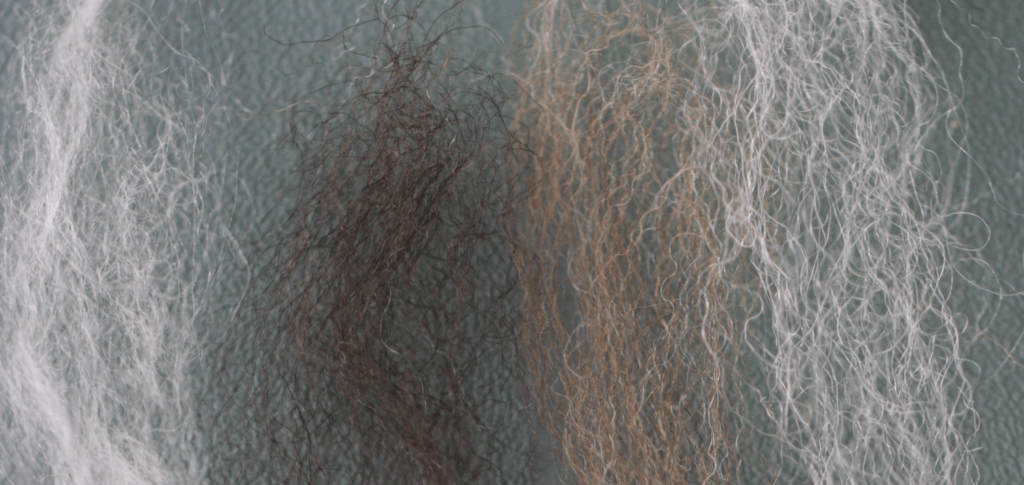

I've also compared it to the Manx Louaghtan, which is an old breed, and to another wool sample that I got for these comparison reasons:

Again the superfine is on the left, followed by my South American test candidate, then the Manx (which appears more saturated brown than in real life) and, for comparison, the Eider wool again. Both candidates are definitely finer than the Eider wool (which should have around 30-33 micron), but considerably coarser than the superduper benchmark.

And here you are. The Bronze Age Fibre Problem, in pictures. The superduperfine wool lacks the coarse fibres strewn in, and has been seriously processed to make it silky, smooth, and shiny. It also is very, very white, and BA fibres are mostly quite heavily pigmented. The two coloured wools have a mix of coarse and fine, but way too many coarse fibres strewn in to match the BA originals. They are, however, nicely pigmented.

So, like with many reconstruction projects, there's the choice between compromises. Use the very fine fibre although it has been heavily processed, dye it, and accept the fact that it lacks the coarse hairs? Try to blend some extra coarse fibres in (it would still need to be dyed)? Or use a wool that is naturally pigmented and not supertreated, but has too coarse fibres, or too many coarse fibres for the amount of fine ones?

Or... would someone please invent a time machine and fetch a handful of Bronze Age sheep? Pretty please?

Detail from the "A(i)lbecunde" Belt from the Diözesanmuseum St. Ulrich & Afra, Augsburg. Tablet-woven from silk.

Detail from the "A(i)lbecunde" Belt from the Diözesanmuseum St. Ulrich & Afra, Augsburg. Tablet-woven from silk.