Textiles sometimes survive in the weirdest circumstances - the Viborg shirt was pulled from a posthole, where it had carbonised (thus the linen fabric has survived). There's textiles that were used as tarring brushes, textiles used as toilet "paper", or those used as wrapping for metal items; in all cases, the coating led to them being preserved better.

Even better when the fabrics are not coated or permeated with something... but are preserved in good conditions. Dry and away from light, and protected from moths and mice and other critters that might have a use for them. Like... pressed between the pages of a book. Such as manuscript curtains.

If you go "huh?" now, that is exactly what I did. A friend pointed this possible source of medieval textile knowledge out to me, as she had heard a talk on the topic in one of the (digital) conferences she attended. And here's one of the little bits of good things the pandemic brought: Because the conference was digital, the talk is available online, on Youtube, and you can get a glimpse of this fascinating practice and, even better, a glimpse of some of the preserved textiles!

Even better when the fabrics are not coated or permeated with something... but are preserved in good conditions. Dry and away from light, and protected from moths and mice and other critters that might have a use for them. Like... pressed between the pages of a book. Such as manuscript curtains.

If you go "huh?" now, that is exactly what I did. A friend pointed this possible source of medieval textile knowledge out to me, as she had heard a talk on the topic in one of the (digital) conferences she attended. And here's one of the little bits of good things the pandemic brought: Because the conference was digital, the talk is available online, on Youtube, and you can get a glimpse of this fascinating practice and, even better, a glimpse of some of the preserved textiles!

Photo from UNIMUS.no

Photo from UNIMUS.no Photo from UNIMUS.no

Photo from UNIMUS.no

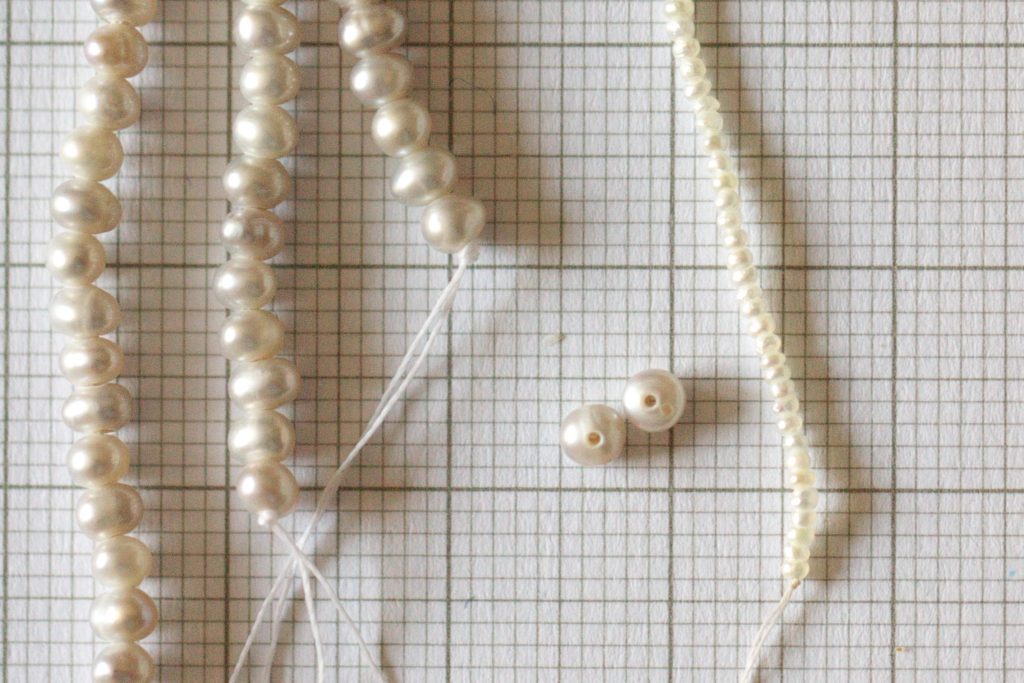

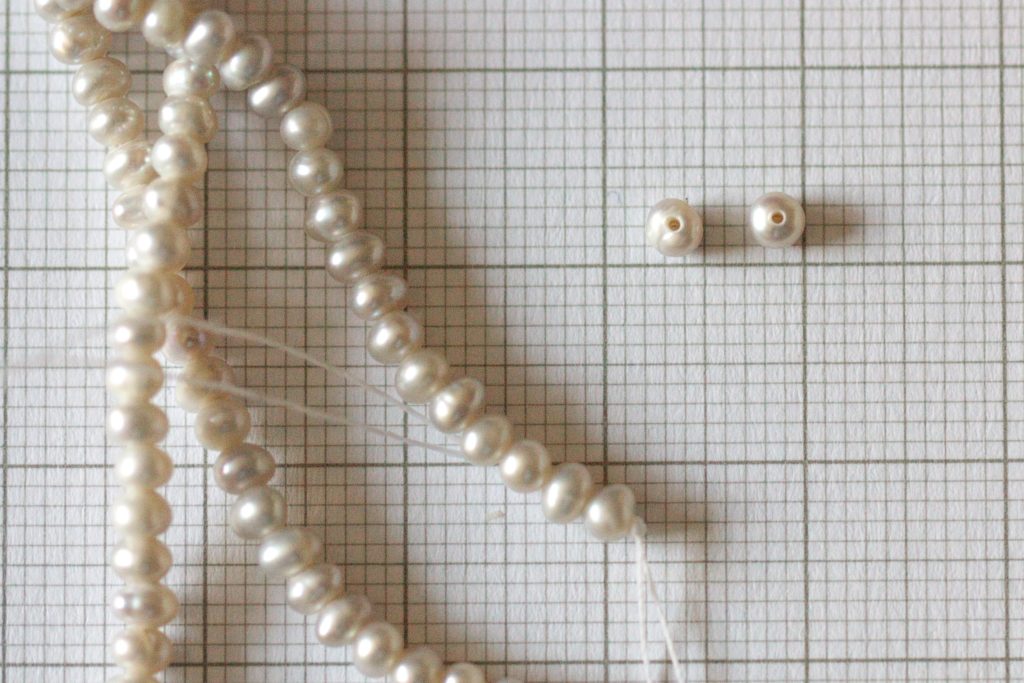

Seed pearls. The backdrop is paper with 1 mm squares.

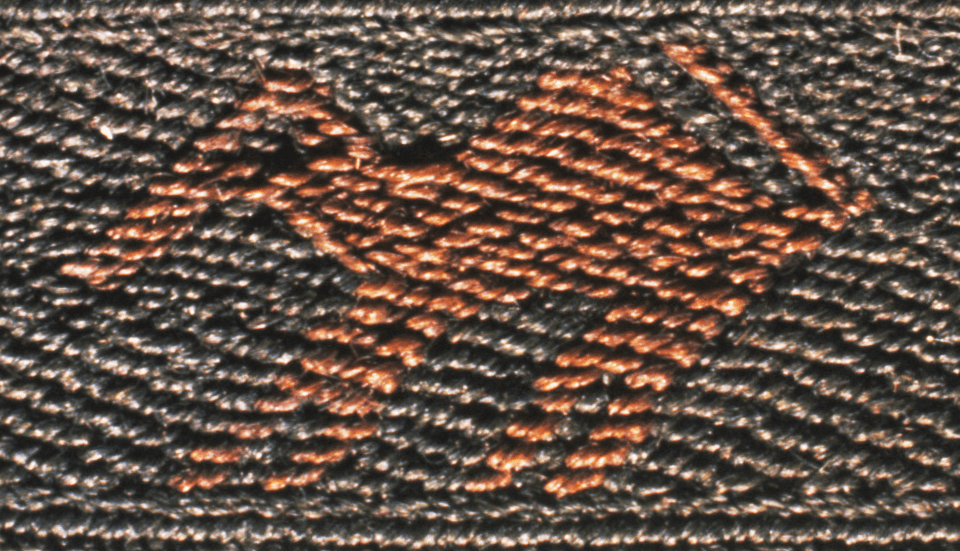

Seed pearls. The backdrop is paper with 1 mm squares. Embroidered container for the Host. Hildesheim, second half 13th century. Wooden core, covered in embroidery with glass, sweetwater seed pearls, corals and metal appliqué on parchment. Schnütgen-Museum Köln, N 42

Embroidered container for the Host. Hildesheim, second half 13th century. Wooden core, covered in embroidery with glass, sweetwater seed pearls, corals and metal appliqué on parchment. Schnütgen-Museum Köln, N 42