One of my upcoming projects is an introductory talk about fabrics used in the Middle Ages, especially for garments. It's an interesting topic, but also a rather large one, and one with a few problematic bits - such as different fabric types only surviving in rather different circumstances, without too much overlap.

I'm also still thinking about what needs to be included in the overview, and what would be especially interesting for Living History purposes. Obviously, there will be a little bit of the general basic stuff, as a refresher for those familiar with basic weaves and as a bringing-up-to-speed bit for those who are not. There's also the thing with wool not being alike, because much depends on what type of wool it is and how it's spun, or silk not being like any other silk, depending on whether it's spun silk or reeled silk, and whether reeled silk has been completely de-gummed or not, so these things will definitely get included.

Another thing I'm planning to cover is complex weaves, because these were part of medieval garment splendour, and even though they are hard to impossible to get these days, it is still important to know about them. So one of my upcoming tasks is to wind my brain around the internal construction of samite and lampas again, and find a good way of explaining these to non-weavers.

Apart from these, I'm still pondering what needs to be included, and what could be especially helpful or interesting for Living History purposes. Is there anything you are wondering about? Or would like to know more about? Let me know (and I'll try to give an answer here on the blog as well as include it in my intro...)!

I'm also still thinking about what needs to be included in the overview, and what would be especially interesting for Living History purposes. Obviously, there will be a little bit of the general basic stuff, as a refresher for those familiar with basic weaves and as a bringing-up-to-speed bit for those who are not. There's also the thing with wool not being alike, because much depends on what type of wool it is and how it's spun, or silk not being like any other silk, depending on whether it's spun silk or reeled silk, and whether reeled silk has been completely de-gummed or not, so these things will definitely get included.

Another thing I'm planning to cover is complex weaves, because these were part of medieval garment splendour, and even though they are hard to impossible to get these days, it is still important to know about them. So one of my upcoming tasks is to wind my brain around the internal construction of samite and lampas again, and find a good way of explaining these to non-weavers.

Apart from these, I'm still pondering what needs to be included, and what could be especially helpful or interesting for Living History purposes. Is there anything you are wondering about? Or would like to know more about? Let me know (and I'll try to give an answer here on the blog as well as include it in my intro...)!

Table, clamp, band. I love this setup - it's quick, easy, versatile, and allows to have a wide choice on how to sit at the band.

Table, clamp, band. I love this setup - it's quick, easy, versatile, and allows to have a wide choice on how to sit at the band.

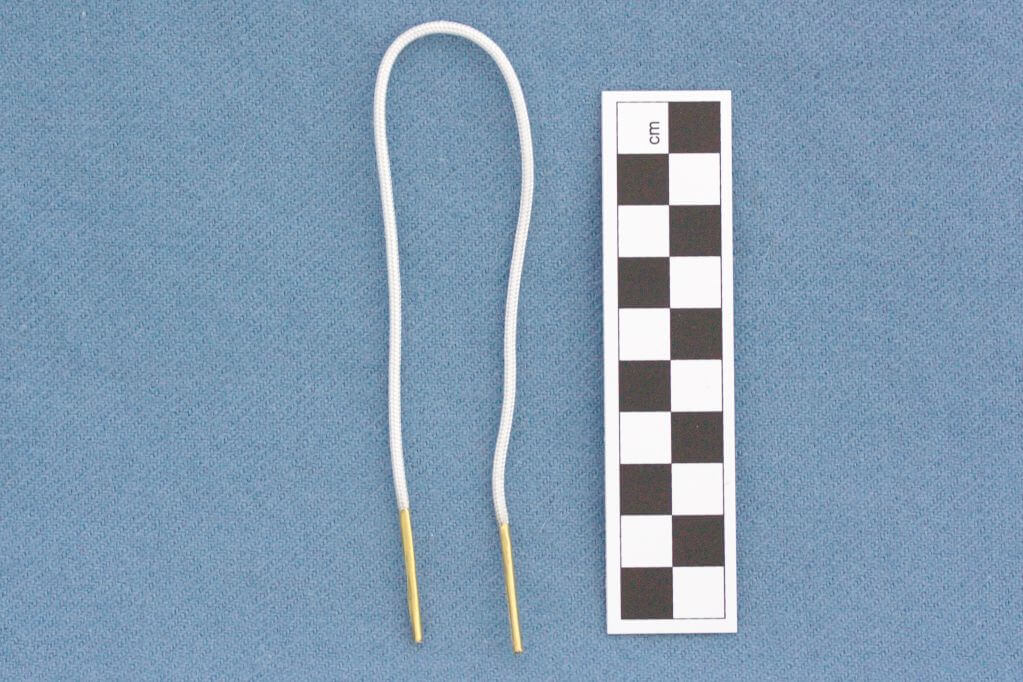

Chapes on a silk lace, braided, 26.5 cm length overall - that is the length from a find from London, and about exactly what you need to make the half-bow knot often seen on late medieval images that holds tunic and hose together.

Chapes on a silk lace, braided, 26.5 cm length overall - that is the length from a find from London, and about exactly what you need to make the half-bow knot often seen on late medieval images that holds tunic and hose together.