It's always nice to find out things... especially when they are connected to medieval textile tools. So when, a while ago, a colleague handed me a reproduction of a weaving knife (or beater, however you opt to call it) from Viking Age Dublin to try out, I was more than happy to do so. It fit in perfectly with my plans to do the tablet-weaving shenanigans... and so I sat down and wove and gave it a try.

Well. Before, I was firmly in the camp of "I just use my finger to beat in the weft, and that's good enough for me". Let me tell you, though: I am not ever going back to that. Well, maybe for a narrow, simple band, where weaving is fast and I'm handling the tablets with one hand and the shuttle with the other and it's more like just speed down the warp, and that's it. But for things like the twill patterning, or wide bands? Aaah. It does make such a difference - and it actually makes a huge difference, for me, to pressing the weft in with some other tool.

In the past, I had tried to use the shuttle edge, or a special small shuttle with a "beating sting" attached to it (which I have mislaid and cannot currently find, which tells you already how much I use it...), or a ruler, or a bone folding tool. None of them cut the mustard for me - they were one more thing to handle, and my finger did not need picking up and setting down in contrast to these all, and made about the same job.

The difference? Size and shape of the new thingie. This is how it looks:

You will note the very broad, very curved blade with the curious indentation at the very tip - things that my colleague found slightly weird. There is a second find from Viking Age Dublin with this shape, so one might surmise that it's not a fluke, but that there is some reason behind it. I had no clue about this possible reason, only a guess regarding the curved blade: It might allow to press the weft in very precisely yet gently, using a rolling motion of the curve across the fell.

Well. That guess certainly proved correct - the tool's form is just perfect to roll it across the width of the band, making sure all the fell is pressed back firmly and evenly. As there is only a smallish contact point, it is easy to apply a little more pressure where necessary and a little less where the warp is softer. Calling this thing "beater" does it no justice at all, by the way - movement and action are all nice and soft and gentle, as befits a delicate tablet weave. With the warp under just enough tension to work well, but not more, beating in the shed would not be a good idea, as it might disorder the tablets. It also puts more stress than necessary on the warp, as well as on the tensioning method - so the curved blade is a total boon.

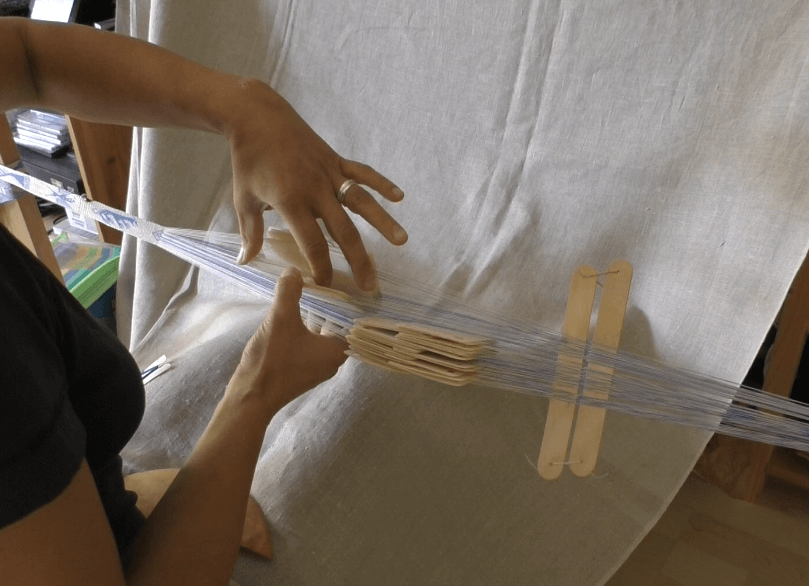

[caption id="attachment_4054" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Gently pressing in the weft.

For this, a smaller tool would actually work for me - but I have also found it wonderfully useful for correcting mistakes.

When I need to go back a pick, I loosen up the last weft, pull it towards the tablets, and then I open the shed it runs through with my fingers. I then usually stuck something in there - my finger (which binds one hand, so not very good for longer or more complex corrections), some stick, or whatever (a bone folder, for instance). The purpose of this is to keep the old shed open to individually turn each tablet back the way it came, re-establishing the position before the mistake. Obviously, it's a) helpful if you see how the threads run over your tool, and b) important that it does not slip out too early. Both of these were, hm, let's call it sub-optimal with a stick or a bone folder.

With the almost 30 cm of total length, and the relatively long blade part, the tool easily accommodates my warp for these corrections. The back of the blade is wide enough to stretch the shed apart nicely so I can see what is happening, and the total length is just long enough to either set the handle's end on my knee or hold it between my legs, making sure it stays put.

[caption id="attachment_4051" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Fixing a mistake by weaving back - the crossings from the previous turn are carried towards the tablets.

Most often (fortunately!) the mistakes are not so bad that I need to go back for the whole pick - they are just one or two tablets that accidentally turned into the wrong direction. Or sometimes, I'm not sure whether the edge of a pattern section is where it is supposed to be. In these cases, I pick out the tablet cord in question close to the fell and follow it back to the stack of tablets. For this, something more pointy and accurate than a finger is very helpful. Bone folders will work, as will needles... but, guess what works even better?

Yes. The pointy tip of the tool. With the indentation making the tip of the blade effectively a lot narrower than the curve would dictate, it is just perfect to pick out the offending place, stick it in and follow the yellow brick road, excuse me, the tablet cord in question back to its origin.

[caption id="attachment_4053" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Catching the questionable pattern section edge to check whether the tablets stand correctly.

It works much, much better than the bone folder. Or a ruler. Or my finger.

It's also not a bad thing that this tool is totally beautifully made, and very smooth, and beautifully decorated with carvings, and made from service tree wood, which is my absolute favourite wood ever.

So worth the extra step of picking up the tool! And in the future, my fingers will not see that fell again... because I'm not going back, nothankyouverymuchindeed.

Gently pressing in the weft.

Gently pressing in the weft. Fixing a mistake by weaving back - the crossings from the previous turn are carried towards the tablets.

Fixing a mistake by weaving back - the crossings from the previous turn are carried towards the tablets. Catching the questionable pattern section edge to check whether the tablets stand correctly.

Catching the questionable pattern section edge to check whether the tablets stand correctly. Notches! From left to right: plain un-notched tip, horizontal notch, diagonal notch for z-spun yarn, diagonal notch for s-spun yarn.

Notches! From left to right: plain un-notched tip, horizontal notch, diagonal notch for z-spun yarn, diagonal notch for s-spun yarn.