The eye, the nose, the neck. Ah well.

First, let me tell you about the main difference, for me, in weaving ass-first versus nose-first: When starting with the nose, I will very easily end up with a baboon ass on the dog because of getting the timing of leg slope start and back slope start not quite right. When starting with the tail, I have a high probability of ending up with a too-thick neck because of somehow fuddling things up in the middle, and then getting the timing for the neck not quite right. I suspect that if woven cleanly, the thick-neck-problem might evaporate. (It's on my list to manage that the next time.)

The nose area, however, is a different beast.

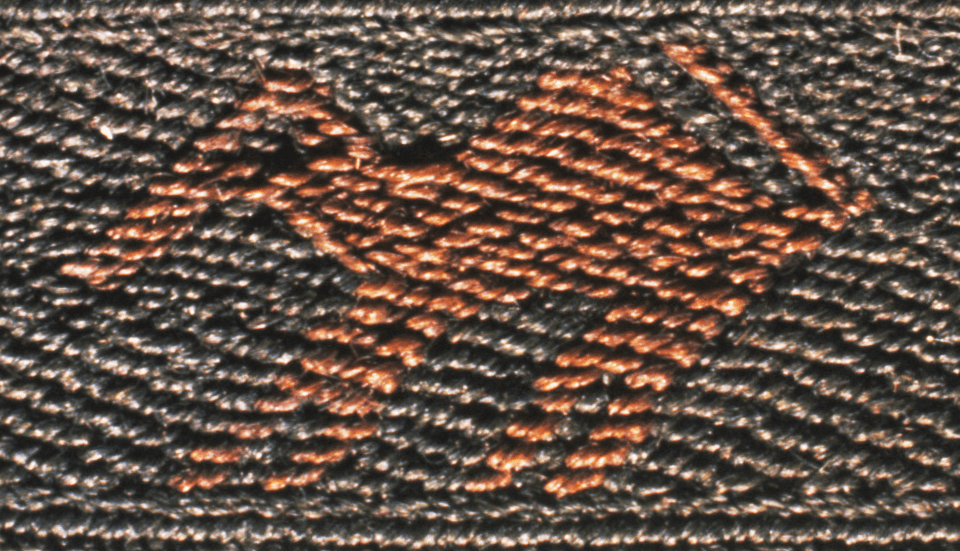

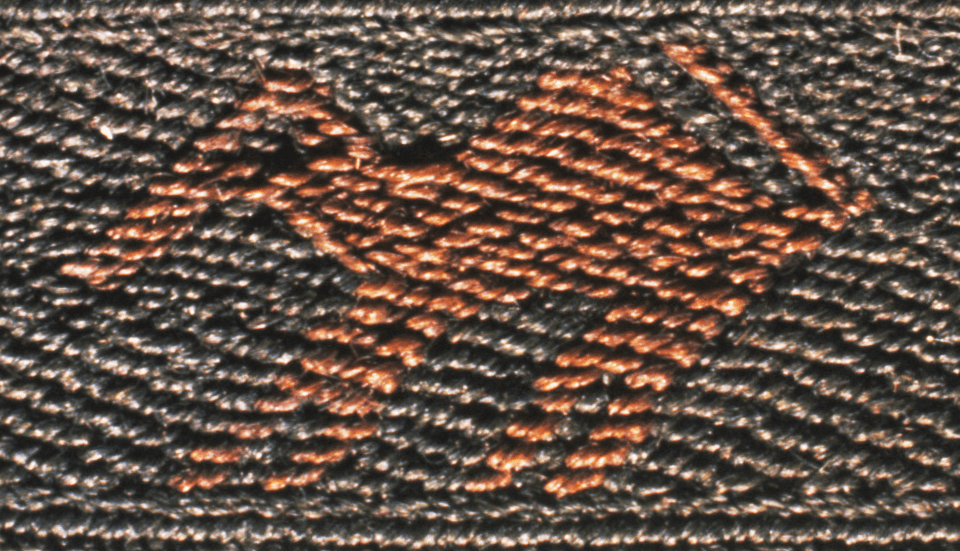

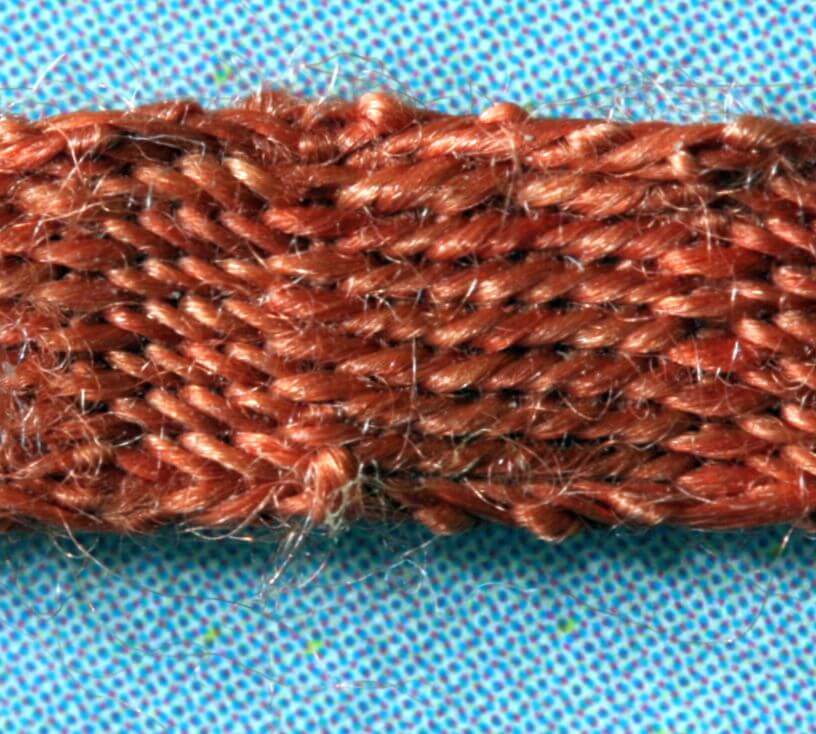

[caption id="attachment_5364" align="alignnone" width="328"] Photo from UNIMUS.no

Photo from UNIMUS.no

[caption id="attachment_5365" align="alignnone" width="441"] Photo from UNIMUS.no

Photo from UNIMUS.no

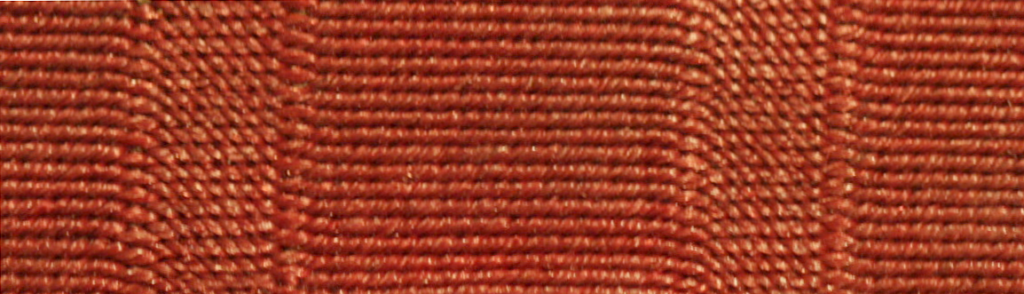

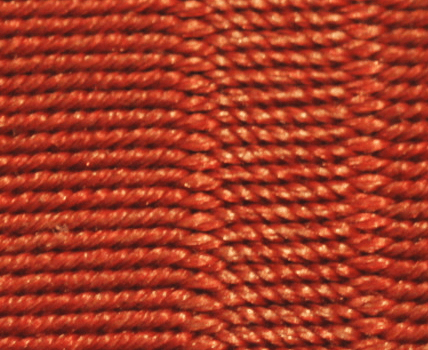

If you compare the look of the back of the band in the tail and leg region, you can see that there is a characteristic look of broken narrow lines - that's the back of the regular diagonals structure, which is exactly what we have on the front for a while: white, purple, white, purple.

The noses on my dogs are all one of these regular stripes as well - white, purple, white; a single (two-thread) line on top of the band, and the regular broken line on the back. Except in the very first dog, where I did a wide nose.

Now, the rules of normal twill dictate that a line you "draw" on the background is either one line (two thread's worth) wide, or three lines (in order to go out with a nice clean line again). Three lines because you have, in the diagonal base setup, a white line coming out of the twill, then your pattern dark line, a light line, a dark line, and then a white line going back into twill again. For a wider line, you cover up the light between the two dark lines by change of tablet turn direction, but you still have to weave into the regular dark line to get a clean shape. So. Two or six is the choice you have.

The original animal's nose is wider than a single line (of two threads) and much more narrow than a regular wide line, though, and that is technically not possible without doing Strange Things (TM).

I suspect the sneaky and ingenious use of some double-turns here, to get the effect. I'm not sure yet how and where they need to get started, though. This is one of the cases where I'll actually sit down with pen and paper and start drafting this to see where lines meet normally, and where lines have to start, or change, to get the desired effect.

And then I can see another dog-weaving stint in my future...

(By the way, in case it interests you: If I don't make silly mistakes and have to weave back, weaving a doggie takes me about one and a half hours. Do try this at home, but not late in the evening when tired, especially not late in the evening when tired plus distracted by other stuff going on in the room that you feel the need to participate in while making silly mistakes in your weaving.)

First, let me tell you about the main difference, for me, in weaving ass-first versus nose-first: When starting with the nose, I will very easily end up with a baboon ass on the dog because of getting the timing of leg slope start and back slope start not quite right. When starting with the tail, I have a high probability of ending up with a too-thick neck because of somehow fuddling things up in the middle, and then getting the timing for the neck not quite right. I suspect that if woven cleanly, the thick-neck-problem might evaporate. (It's on my list to manage that the next time.)

The nose area, however, is a different beast.

[caption id="attachment_5364" align="alignnone" width="328"]

Photo from UNIMUS.no

Photo from UNIMUS.no[caption id="attachment_5365" align="alignnone" width="441"]

Photo from UNIMUS.no

Photo from UNIMUS.no

If you compare the look of the back of the band in the tail and leg region, you can see that there is a characteristic look of broken narrow lines - that's the back of the regular diagonals structure, which is exactly what we have on the front for a while: white, purple, white, purple.

The noses on my dogs are all one of these regular stripes as well - white, purple, white; a single (two-thread) line on top of the band, and the regular broken line on the back. Except in the very first dog, where I did a wide nose.

Now, the rules of normal twill dictate that a line you "draw" on the background is either one line (two thread's worth) wide, or three lines (in order to go out with a nice clean line again). Three lines because you have, in the diagonal base setup, a white line coming out of the twill, then your pattern dark line, a light line, a dark line, and then a white line going back into twill again. For a wider line, you cover up the light between the two dark lines by change of tablet turn direction, but you still have to weave into the regular dark line to get a clean shape. So. Two or six is the choice you have.

The original animal's nose is wider than a single line (of two threads) and much more narrow than a regular wide line, though, and that is technically not possible without doing Strange Things (TM).

I suspect the sneaky and ingenious use of some double-turns here, to get the effect. I'm not sure yet how and where they need to get started, though. This is one of the cases where I'll actually sit down with pen and paper and start drafting this to see where lines meet normally, and where lines have to start, or change, to get the desired effect.

And then I can see another dog-weaving stint in my future...

(By the way, in case it interests you: If I don't make silly mistakes and have to weave back, weaving a doggie takes me about one and a half hours. Do try this at home, but not late in the evening when tired, especially not late in the evening when tired plus distracted by other stuff going on in the room that you feel the need to participate in while making silly mistakes in your weaving.)

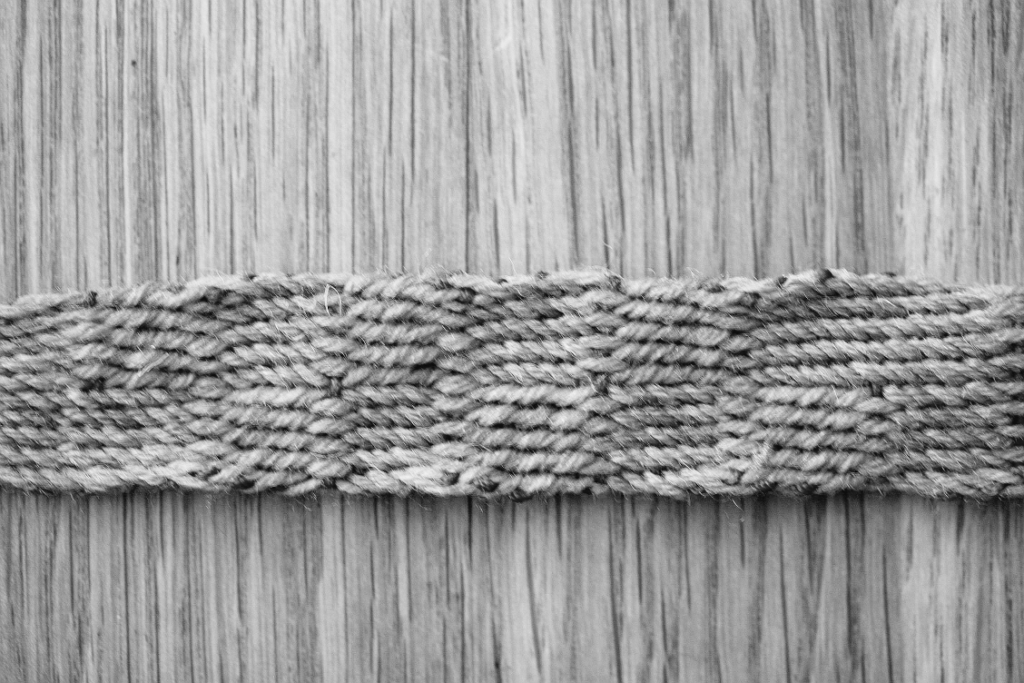

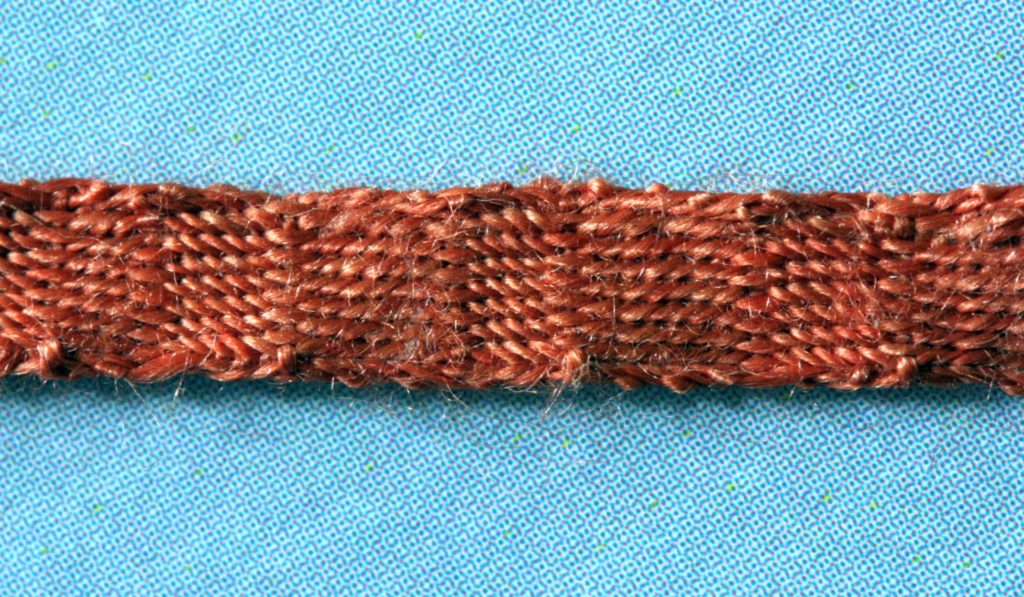

Reconstruction of the Bernuthsfeld tunic, made for the museum in Emden by Jens Klocke and myself.

Reconstruction of the Bernuthsfeld tunic, made for the museum in Emden by Jens Klocke and myself.